Abdominal pain in the equine is generally referred as colic. Colic is a true medical emergency and requires immediate veterinary attention. This condition may result from a variety of primary and secondary causes, many of which are included in the following:

1. parasitism, especially large stronglyes (perhaps 80-85% of all colic)

2. nutritional factors such as feed high in fiber or poor in quality; sudden changes in feed;

and feed too high in energy

3. improper chewing; caused by poor teeth or mouth injuries

4. systemic disease, accompanied by fever and decreased feed and water consumption

5. circulatory disturbances such as embolism, infarction, and toxemia

6. digestive system infection, resulting in excessive gas production

7. neuromuscular disturbances

8. volvulus or torsion (twisting of the intestine)

9. lipomas (fatty tumors)

10. gastric dilation caused by grain overload toxicity or bots

The pain of colic is caused by obstruction of the ingesta, resulting in increased gas production that stretches the intestines, or by hyperactive peristalsis, i.e., spasms in the alimentary canal.

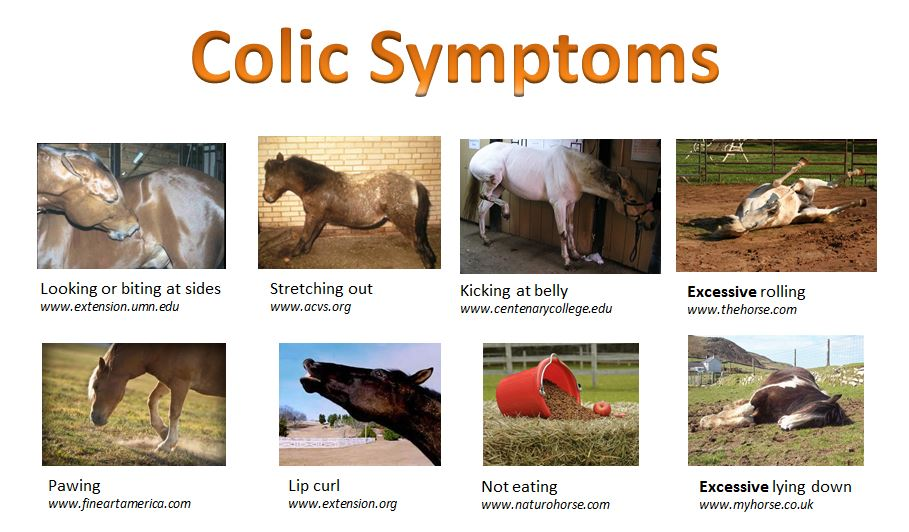

There are several characteristic signs that may be used in identifying suspected colic; these include:

1. lack of appetite

2. unusual attitudes or behavior

a. biting at flanks

b. kicking at the stomach

c. lying down

d. rolling

e. restlessness

f. anxious expression

g. pawing

3. elevated skin temperature

4. sweating

5. increased and/or thready (weak, uneven) pulse

6. abnormal mucosa color

7. abnormal gut sounds

8. abnormal feces or lack of feces

9. rising hematocrit (packed cell volume)

The expression of these signs varies with the individual horse and the particular kind of colic involved. However, the veterinarian should be contacted when a case of colic is suspected, as it is impossible to differentiate between mild and serious cases when they first appear. In particular, obstructive colic must be surgically corrected as soon as possible to give the horse its best chance of recovery.

Suspected cases of colic require veterinary diagnosis and/or treatment. In each case, the horse should be kept calm and relaxed until the veterinarian arrives. A horse that will stand or lie quietly should be allowed to rest. If the animal begins to roll, it should be coaxed to its feet and walked, preferable over a soft, grassy area, to reduce the chances of injury or twisting of the gut. Obstructive colic, which causes severe, unremitting pain, may cause the horse to become extremely violent, in which case the animal's handler should be careful to keep safely out of the way.

Banamine or phenylbutazone are often administered by the veterinarian to relieve the pain of colic. Dipyrone, an analgesic anti-inflammatory drug is also commonly used. In nearly all cases, mineral oil will be administered through a stomach tube.

In addition, to facilitate elimination, the veterinarian may administer a fecal softener. After the treatment, it is often recommended that the horse be walked until he begins to properly eliminate feces. The hematocrit may be monitored during treatment, as a rise in hematocrit indicates the need for intravenous fluid therapy. The veterinarian may administer as much 20 liters in an hour. The horse should be carefully watched for at least 24 hours after the signs of colic are relieved, because the condition may recur. The grain ration should be reduced considerably at the next feeding, and bran may be added as a laxative. The horse's feed should then be gradually increased over a period of several days until the normal amount is reached.

%20(1).png)

Comments